14 Sep 2018

•

Review

I finally read Man’s Search for Meaning, by Victor E. Frankl. I have heard people recommend this book repeatedly over the years, most recently by my therapist.

The first part of this book (a hundred pages) tells the story of Frankl’s experience as a prisoner and forced laborer for years in German concentration camps during World War II. Frankl, a psychiatrist, wanted to understand why some fellow prisoners appeared to transcend their suffering and survive, despite being brutally stripped of their humanity and everything they held dear, while others lost the will to live. His matter-of-fact account of these brutal memories was almost traumatic to even read. His writing is at once human and transcendant.

The remainder of the book (fifty pages) presents a description of his resulting philosophical view, known as logotherapy. Logotherapy is the model he fit to the suffering prisoners who transcended. The distillation includes a brief summary of the core ideas, guidance around life application, common objections and answers, and pitfalls to avoid. He includes practical stories from his clinical experience.

The first thing I need to say is that, no matter how much I read about genocide, I find it hard to accept the reality of evil that leads to this type of horror. The fact that this pattern continues to replicate across time and cultures multiplies the urgency that we should feel. Despite the modern comforts of the West, this evil will one day knock on our door again and history will ask: Have you learned nothing?

I also experienced my other well-worn reaction to accounts of extreme suffering, which goes like: “I will never complain about my life, ever again.” Of course, the shock wears off and I regress to the mean, but I try to hang on to this somehow.

The core idea of Frankl’s philosophy is expressed in its name: logotherapy. Logos means “meaning”. Thus, the fundamental work of logotherapy is to connect to a greater meaning and live within this orientation.

I’m going to try to summarize my personal takeaways briefly.

He’s fond of quoting Nietzsche: “He who has a why to live can bear with almost any how.”

The three sources of meaning he identifies are: (a) creating a work or doing a deed, (b) experiencing something or encountering someone (i.e. love), and (c) rising above suffering / turning a personal tragedy into a triumph. In another essay, he presents a case for optimism in the face of inevitable tragedy around (a) turning suffering into a human achievement, (b) harnessing guilt as a driver of personal improvement, and (c) embracing life’s transitoriness as a driver of responsible action.

One of the ways you uncover meaning in hard circumstances is by studying the stories of those who have endured similar suffering in order to understand how they found meaning vs. those that did not (biographical approach).

One distinction I liked was that he views struggle caused by mere existential distress (around lack of meaning) as much more common than genuine clinical mental health disorders. And that even in the case of mental illness, the psychosis does not destroy the core personality of the patient, but rather an expression of genuine freedom always remains, along with human dignity. Along these lines, he claims a goal of rehumanizing psychiatry.

One good example of this he talks about are “employment neuroses”, basically the idea that people languish mentally when they are out of work and feel they have no use to society. I will just say that I have seen some friends get lost in this experience and also seen the clouds open up immediately as they reentered the work force. There was no mental illness (or at least related to that), but rather a basic system in their life that was off the rails and needed correction. Seems straightforward.

Frankl and colleagues viewed Americans, even back then, as being overly obsessed with being happy. His advice here: If you make happiness your target, you will fail. If you make meaning your target, you will gain both purpose and happiness. Happiness cannot be gained if directly sought.

In summary, I thought it was a remarkable book and one that I could benefit a lot from internalizing. Every page contains quotable soundbytes or moving accounts of human

02 Sep 2014

•

Philosophy

How do you know what you believe?

The best heuristic I’ve come up with this: You believe something if your life is constrained by it. This includes your actions, decisions, thoughts… basically what you have control over. Like a guard rail, if you intersect the boundary of one of your beliefs, an invisible force will reign you in and prevent you from trespassing. You are constrained by your belief.

I don’t claim this is the only or best way to measure belief, but I think it works to a point. Thinking about belief this way has been both encouraging and disconcerting. It has revealed some interesting insights, including things I want to believe but don’t, as well as things I do believe but frankly wish I didn’t.

This doesn’t just apply to spiritual beliefs–it works just as well for everything else.

26 Aug 2014

•

Rules

Like you, I am an above-average driver. I achieved this status by inviolable personal rules.

Driving is almost definitely the most dangerous thing I do in a given day. Nothing puts me, my wife, or my kids at greater risk. We live in a culture where it’s socially acceptable to drive while rushed, stressed out, and distracted. How are any of us still alive?

It occurred to me the other day that I have already started teaching my 5 year-old daughter how to drive. I teach her every day what is okay by what I do. So I got to thinking about it and realized I have a series of rules I follow (and should follow more strictly) that I want to be second nature to her years before she ever touches a set of keys. I have started using these rules by name with her. I’m writing them up to codify them for myself.

Remember Physics (Momentum, kinetic energy, etc.)

Driving is probably the most important reason the everyman took physics in high school. If you understand kinetic energy and momentum and don’t focus all your attention on the road while driving, there is nothing I can do to help you. Do your part in reducing the necessary energy dissipation required on your side of the equation to save your and other peoples’ lives. You can’t control how fast the person you hit is driving, but you can slow down a little bit.

By the way, this rule has less to do with how fast you drive and more to do with how serious and focused you stay while driving.

Respect The Wall

What is The Wall? The Wall is an invisible 10-ft tall, 2-ft wide brick wall running down the centerline of every street. Even though you do not see it, The Wall is there. So why not cut a corner turning into your neighborhood? For obvious reason: You will crash your car into the massive brick wall there.

Driving through your tranquil neighborhood and tempted to cut the corner into your cul-de-sac? Respect The Wall.

Driving the only car in an empty parking lot in the middle of Montana at 3 o’clock in the morning? Respect The Wall.

We fail to respect The Wall because respecting The Wall isn’t convenient, because we are lazy, because we let the rush we are in overtake our responsibility to protect ourselves, our passengers, and whoever else is on the road.

We violate The Wall because we think we can see well enough to know there isn’t a car coming (or won’t be eminently). But here’s the thing: I’m not that confident in my ability to anticipate every hidden drive or unexpected circumstance.

If you strike a car while violating The Wall, it is your fault, emphatically your fault. You broke the rules, not the person you just hurt. Never driving in someone else’s lane has to drastically reduce the probability of getting in an accident.

I try to only break this rule for obvious exceptions, and only after I am completely sure it is safe: passing cyclists, giving extra margin to playing kids, and the like.

Delete Risk from Your Map

We’ve all driven through certain intersection sor made a turn where higher-than-normal risk is involved. Visibility is limited. A light doesn’t give enough time. You have to do something where you don’t feel in control. You have to expose yourself before you can see if the coast is clear.

Once I identify a stretch of road or intersection like this, as much as it is in my power, I never go that way again. The rule: I delete it from my map.

Example: There are precisely three ways to access my neighborhood when driving home from work. I only use two of these, ever. Zero exceptions. The third has a short turn light and people tend to get stranded in the intersection and make stupid moves—this intersection was ranked in an article I read as one of the 10 most dangerous intersections in Massachusetts based on fatality data.

So it’s gone. Dead to me. Deleted from my map. Inasmuch as I can help it, I will never go that way again.

It Can Wait

Receive a text while driving? It can wait.

Get a call while driving? It can wait.

Confused thinking my GPS is sending me the wrong way? It can wait.

Forgot to tell your wife something after pulling out of the driveway? It can wait.

Spill your coffee? It can wait.

Your kid dropped their breakfast on the floor? It can wait.

It can wait the two minutes it will take for you to find a safe place to pull over and text back, call back, and salvage the spilled food.

Drive Painfully Slow in Neighborhoods where Kids Play

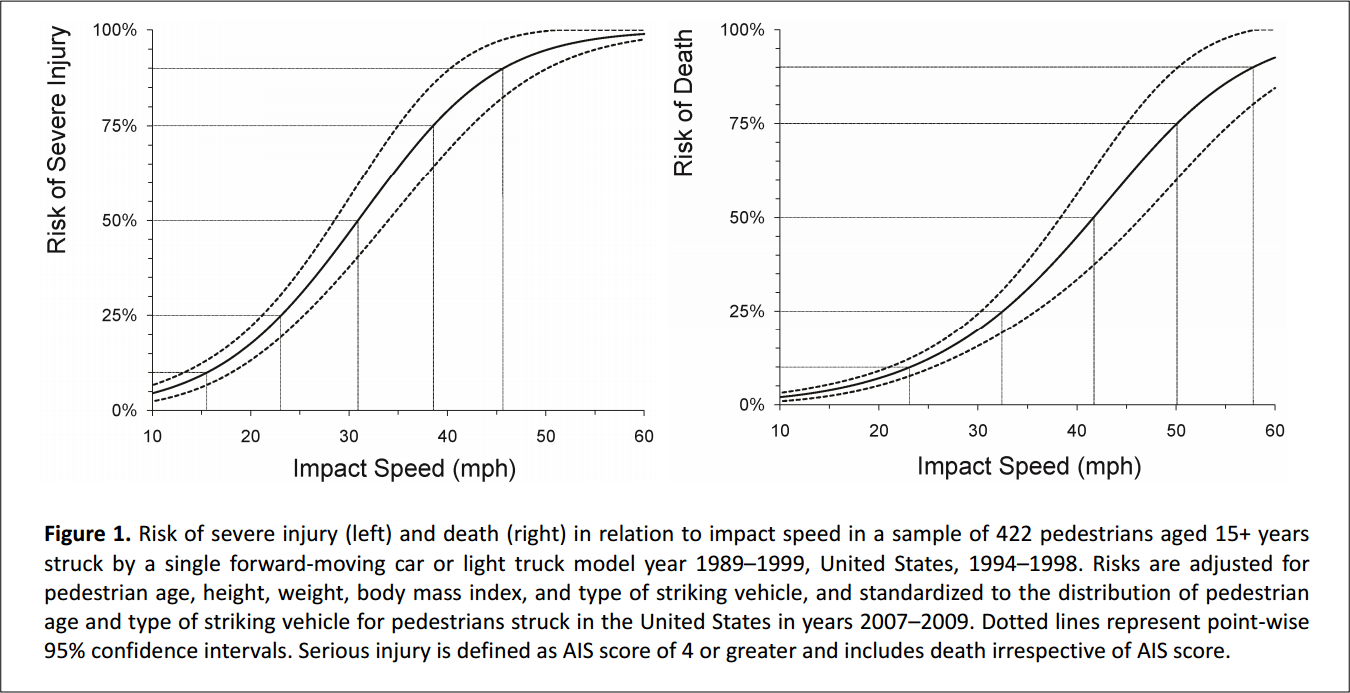

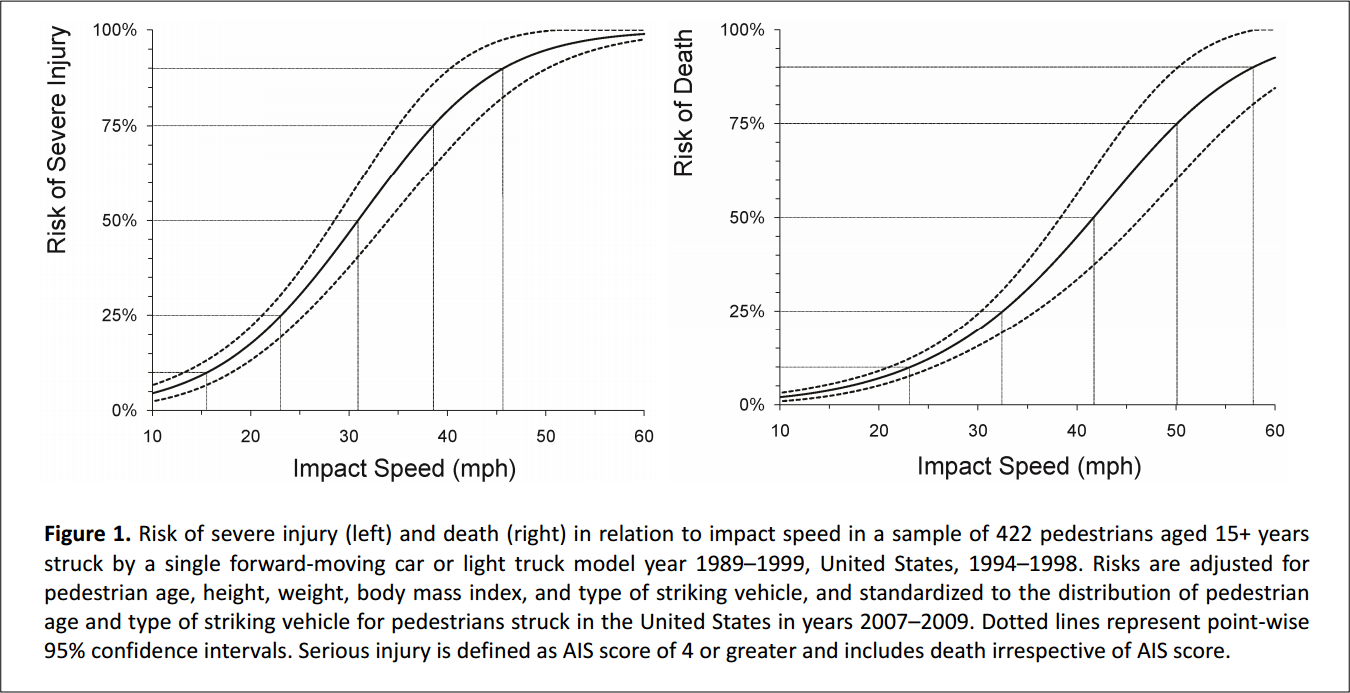

When you are in a neighborhood where there is virtually ANY chance a running kid could chase a rolling ball into your path, drive no faster than 10 or 15 mph. Driving slower reduces your stopping distance as well as the risk of severe injury to a pedestrian you strike. The probability of severely injuring a pedestrian is very low when the impact speed is less than 10 mph. On most graphs I saw during a cursory lit review, the probability of death jumps from 10% to 75% between 20 and 50 mph. Here are the cumulative distribution functions from one study I found:

Whether you agree with the methods of that (or any) particular paper, wouldn’t you feel better knowing that people in your neighborhood (where your 5 year-old plays) were driving 10 mph? I sure would.

Conclusions

So that’s it, just a humble plea to be a bit more mindful when driving. Thanks for reading.

20 Aug 2014

•

Miscellany

I have had a longstanding rule when flying that if I do not run through the airport at some point, I arrived too early. I’d generally rather be outside the airport exploring whatever city I’m in, for as long as I can, with people I like. The benefits of sprinting are numerous and equally applicable within airports.

But Craig Mod might have just changed my mind. Excellently written and derived via an impressive history of international travel, he shares his practical—and very funny—approach to getting from A to B with minimal stress and optimal enjoyment.

You look insane — your white mask, your monkey bra, your noise-canceling headphones, but it doesn’t matter. You are satiated, filled with nourishing food; you have gotten your work done, and now you float in a personal outer space. An outer space that sounds like the summer in Wisconsin and feels just as humid within the nose and mouth thanks to your microclimate. You are on a plane but are not. You could be anywhere. You are untouchable. You are possibly the most insufferable traveler ever. You float and smile because you are the Dalai Lama. This is how you survive air travel.

07 Aug 2014

•

Learning

I want to talk a bit about challenging financial situations today and some resources I have found most helpful. First, some context. The parameters of our move to Boston included the following: (a) a moderate level of student loan debt, (b) expenses incurred in support of a cross-country move and settling into a new place, (c) a 3-4 month waiting period before finding a suitable renter for my home in Atlanta, and (d) high housing costs in Boston (I pay 2x for 0.5x space relative to Atlanta).

I won’t discuss specific numbers, but suffice it to say the bottom line after the dust settled from all this was overwhelming. I have known people who were facing many times the debt I faced. It’s difficult to even know where to start. Dealing with that level of challenge required a complete reboot in my thinking and approach to money.

Aside for potential grad students: By the way, this is an especially important topic for people coming out of grad school with a PhD. You may have an idea that you are now a very big deal and carry an unrealistic perspective on your earning potential (there is probably a reality check waiting for you, even in STEM fields). And you are also entering the financial game years behind your friends who only did an MS or MBA, which means you are already five years behind in terms of both lost income and compounding interest. I’ve heard it said that a Ph.D. roughly costs you a paid-off house in lost income.

My wife and I paid it all off in about a year. We found that once you become willing to make very difficult changes, you make progress faster than you think you will.

So, if you are in a similar boat and in the mood to get trounced, here are some resources that helped me take responsibility and make difficult and necessary changes:

The Total Money Makeover (Ramsey)

The Dave Ramsey debt snowball concept from this book is the number one tool that kept me motivated as I paid down credit cards and student loans. Reading this book initiated the process toward a whatever-it-takes mindset. I sold things I thought I’d never be able to let go of: my road bike, my iPad, a nice watch, and countless other things I previously felt entitled to. Does your family actually need two cars? I came to view those things as items I simply could not afford, no matter what justification I previously came up with. I don’t normally prefer a writing style like Ramsey’s, but frankly I thought it worked in this context. Cannot recommend highly enough.

Boundaries: When To Say Yes, How to Say No (Cloud and Townsend)

Here is a book that is ostensibly about maintaining a healthy relationship to all the various parameters in your life: people, work, health, yourself, etc. What am I personally responsible for in my key relationships? What am I not responsible for in my key relationships? This book touches every major area of life. But I found this book had a remarkable impact on my view of money and the personal responsibility I must take on with it. If I am in debt, it is a result of my decisions and actions. No one is going to bail me out, and the outlook will not improve until I own the situation, devise a plan, and walk it out daily over a long period of time. Ignoring a problem is unacceptable.

If You Can: How Millennials Can Get Rich Slowly (William Bernstein)

This is an outstanding short (30 min) read that markets itself as an investment primer for millennials. Here is a book that will show you why you have to eradicate your debt ASAP: you must start investing ASAP. If you cannot find the discipline to save, it does not matter how much money you make. It is full of practical advice and is a springboard to other, more in-depth, resources on personal finance and investing.

The Millionaire Next Door: The Surprising Secrets of America’s Wealthy (Stanley and Danko)

I read this book because I have heard time and time again that if The Millionaire Next Door will not win you to frugality, then nothing will. What is the message? Many people who appear to be wealthy aren’t. Many people who are wealthy appear not to be. People who have truly taken responsibility for their financial future have no need for (and definitely do not feel entitled to have) “status artifacts”. Instead, and among a great many other activities, they live simply and spend significant time and resources planning for the future.

Seth Godin has written a handful of no-nonsense posts on personal finance. Seth rightly treats consumer debt as the emergency it is and offers practical suggestions to change. I also love some of his generally mentality which leaks through in these posts.

A few comments on personal finance blogs:

My advice is to mostly stay away from them unless they really tow the frugality line like the Get Rich Slowly. I have found much financial writing which purports to help, instead subtly reinforces the mentalities that breed an indebted lifestyle. Instead of teaching you to take responsibility for your actions and make sacrificial changes, they distract you with “hacks” that never address the core problem or still tempt you to spend money. For example, you should be more concerned about becoming expert in your current field than getting your passive income gig off the ground. But that message probably doesn’t drive page views.

A few comments on tools:

You don’t have to spend a dime to make massive changes for the better. It’s tempting to rationalize further purchases off the bat that will help you meet your goals. This software or those fancy envelopes for your cash-only system. Don’t fall for it. You have to stop rationalizing spending. Every book listed above is available at your local library. All the tools you need are basically free: Mint.com, Excel, a Google spreadsheet, envelopes for cash (okay, $1).